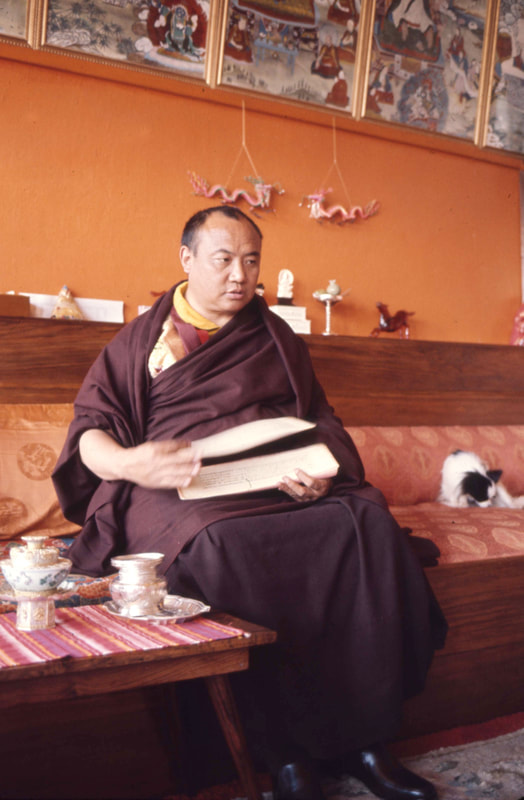

Karmapa in Rumtek, around 1966. Phtoto: Alice Kandell. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. LC-DIG-ds-04112

A Visit in Rumtek in 1965

Excerpt from: Doig, Desmond: Visitors Step From 20th Century When They Enter Monastery In Sikkim, The Cincinnati Enquirer, May 16, 1965.

WE WERE invited into the monastery building by our English-speaking friend. It was dark inside. Only one large butter lamp burned on the altar, but the gloom enhanced the beauty of things half seen: gilded deities wearing jeweled crowns, the sacred scriptures wrapped in silk; murals and painted banners.

In front of the high altar were two brocaded thrones. One. more elevated than the other, belonged to his holiness the Gyalwa Karmapa Lama, a refugee from Tibet.

From the chapel we clambered up well-worn wooden stairs to the private apart-

ments once occupied by the Karmapa Lama. One room had been converted to a dispensary.

"Obviously a lot of dysentery about,” remarked a doctor among us as he took stock of the modern drugs and bottles of brightly colored medicine. The main upstairs room contained a throne much like the one in the chapel, brocaded cushions set upon wood, and an altar on which were row upon row of beautiful gilded images, among them likenesses of former bodies of the Karmapa Lama. A monastery cat sunned itself by the window. A cageful of birds was on the floor.

HIS HOLINESS has a passion for birds and animals and the place is full of them, chattering budgerigars in the old living quarters, a pair of Pekingese dogs in the new residence, canaries

singing in the private chapel, nondescript black and well-bred Siamese cats sitting pompously on Tibetan rugs in the presence of the master.

From the old monastery building, with its magnificent views of Gangtok and the high, snow-capped peaks beyond, it is a short walk to the new yellow-roofed residence of his holiness. We were greeted by a number of lamas who led us upstairs to a waiting room adorned with gay carpeted seats and a puffed-up Siamese cat. His holiness, we were told, would receive us.

Minutes later we were crowded into a small room and into the smiling presence of the Gyalwa Karmapa Lama. He was perhaps 30 years old, plump, a polished gold in color. He exuded a pious good nature and was dressed in magenta robes.

Behind him were the familiar brocaded cushions and the gilded altar, the jeweled deities, silver butter lamps, offerings of water in silver cups and a magnificent prayer wheel. Indicating the carpeted settees against the walls, his holiness asked us to sit down. Immediately we were offered boiled sweets and biscuits by an attendant lama, the Karmapa blessing them before they were served.

WE TALKED by way of a lama interpreter. An Ameican woman writer wanted to know if, in the changing world of Tibetan Buddhism, there would be a relaxing of the rules that barred women from living in monasteries. The lama’s eyes popped, then he laughingly replied that the lady might care to become a nun. When she said yes, she would, he reminded her that the nunnery was some miles removed from the monastery.

Did his holiness agree that some taboos such as that on birth control in the Catholic Church and on casteism in Hindu India, require revision? And did his church have any such taboos?

There are no new problems, the lama replied. They have always existed and the enlightened man of God has found a way around them as they present themselves. The Buddha said that there are many roads to perfection and that the ways are long and have many bends. If religious leaders are finding satisfactory answers to the particular needs of today, it is as it should be.

We asked for the lama’s blessing before we left. An attendant produced two lengths of diaphanous cloth, shocking pink and smoky blue. The Karmapa cut them into short lengths, knotting each one at its center with a quick pass of his delicate hands, then blowing on it. As we bowed before him, one at a time, his holiness swiftly tied a length of the now-sacred cloth about our necks, and smilingly shook our hands. “You’re very lucky,” said the English-speaking lama. “Now you will live forever.”

THERE WAS still the new monastery to visit, half a mile above old Rumtek. It had been a building for seven months and will take another seven to complete. But because it is being built by pious volunteers and because the Sikkim government is giving unstinted help, the construction is well ahead of schedule. The stout concrete walls are complete, rising in four well-proportioned tiers to what will be a golden final. There are an enormous assembly hall, three chapels, apartments for lamas, guest rooms, and a suite for his holiness, its windows framing magnificent views. Though it’s being built of concrete, the monastery is in typical Tibetan style and once it’s painted by lama artisans, it will look like other Tibetan monasteries.

The remarkable thing about the design is that it is contained in the head of an overseer lama. (It was actually Karmapa himself who instructed how this model had to be built, and he was the mentioned ‘overseer lama’). There are no blueprints, only a small cardboard model of the facade. Stress, strains, proportions dictated by astrologers and religious considerations, plumbing, and all the other details are the responsibility of the lama who welcomed us at the site.

A celebrated American architect who was with us thought the building was excellent. He was particularly impressed by the use of space. “Very nice, like heaven,” said our English- speaking friend.

On the way back, we stopped by the roadside to have a picnic lunch and broke the spell. An American diplomat produced onion thins and Danish pate. Someone contributed beer. The 20th century came whooshing back as we opened the cans and bottles.

Excerpt from: Doig, Desmond: Visitors Step From 20th Century When They Enter Monastery In Sikkim, The Cincinnati Enquirer, May 16, 1965.

WE WERE invited into the monastery building by our English-speaking friend. It was dark inside. Only one large butter lamp burned on the altar, but the gloom enhanced the beauty of things half seen: gilded deities wearing jeweled crowns, the sacred scriptures wrapped in silk; murals and painted banners.

In front of the high altar were two brocaded thrones. One. more elevated than the other, belonged to his holiness the Gyalwa Karmapa Lama, a refugee from Tibet.

From the chapel we clambered up well-worn wooden stairs to the private apart-

ments once occupied by the Karmapa Lama. One room had been converted to a dispensary.

"Obviously a lot of dysentery about,” remarked a doctor among us as he took stock of the modern drugs and bottles of brightly colored medicine. The main upstairs room contained a throne much like the one in the chapel, brocaded cushions set upon wood, and an altar on which were row upon row of beautiful gilded images, among them likenesses of former bodies of the Karmapa Lama. A monastery cat sunned itself by the window. A cageful of birds was on the floor.

HIS HOLINESS has a passion for birds and animals and the place is full of them, chattering budgerigars in the old living quarters, a pair of Pekingese dogs in the new residence, canaries

singing in the private chapel, nondescript black and well-bred Siamese cats sitting pompously on Tibetan rugs in the presence of the master.

From the old monastery building, with its magnificent views of Gangtok and the high, snow-capped peaks beyond, it is a short walk to the new yellow-roofed residence of his holiness. We were greeted by a number of lamas who led us upstairs to a waiting room adorned with gay carpeted seats and a puffed-up Siamese cat. His holiness, we were told, would receive us.

Minutes later we were crowded into a small room and into the smiling presence of the Gyalwa Karmapa Lama. He was perhaps 30 years old, plump, a polished gold in color. He exuded a pious good nature and was dressed in magenta robes.

Behind him were the familiar brocaded cushions and the gilded altar, the jeweled deities, silver butter lamps, offerings of water in silver cups and a magnificent prayer wheel. Indicating the carpeted settees against the walls, his holiness asked us to sit down. Immediately we were offered boiled sweets and biscuits by an attendant lama, the Karmapa blessing them before they were served.

WE TALKED by way of a lama interpreter. An Ameican woman writer wanted to know if, in the changing world of Tibetan Buddhism, there would be a relaxing of the rules that barred women from living in monasteries. The lama’s eyes popped, then he laughingly replied that the lady might care to become a nun. When she said yes, she would, he reminded her that the nunnery was some miles removed from the monastery.

Did his holiness agree that some taboos such as that on birth control in the Catholic Church and on casteism in Hindu India, require revision? And did his church have any such taboos?

There are no new problems, the lama replied. They have always existed and the enlightened man of God has found a way around them as they present themselves. The Buddha said that there are many roads to perfection and that the ways are long and have many bends. If religious leaders are finding satisfactory answers to the particular needs of today, it is as it should be.

We asked for the lama’s blessing before we left. An attendant produced two lengths of diaphanous cloth, shocking pink and smoky blue. The Karmapa cut them into short lengths, knotting each one at its center with a quick pass of his delicate hands, then blowing on it. As we bowed before him, one at a time, his holiness swiftly tied a length of the now-sacred cloth about our necks, and smilingly shook our hands. “You’re very lucky,” said the English-speaking lama. “Now you will live forever.”

THERE WAS still the new monastery to visit, half a mile above old Rumtek. It had been a building for seven months and will take another seven to complete. But because it is being built by pious volunteers and because the Sikkim government is giving unstinted help, the construction is well ahead of schedule. The stout concrete walls are complete, rising in four well-proportioned tiers to what will be a golden final. There are an enormous assembly hall, three chapels, apartments for lamas, guest rooms, and a suite for his holiness, its windows framing magnificent views. Though it’s being built of concrete, the monastery is in typical Tibetan style and once it’s painted by lama artisans, it will look like other Tibetan monasteries.

The remarkable thing about the design is that it is contained in the head of an overseer lama. (It was actually Karmapa himself who instructed how this model had to be built, and he was the mentioned ‘overseer lama’). There are no blueprints, only a small cardboard model of the facade. Stress, strains, proportions dictated by astrologers and religious considerations, plumbing, and all the other details are the responsibility of the lama who welcomed us at the site.

A celebrated American architect who was with us thought the building was excellent. He was particularly impressed by the use of space. “Very nice, like heaven,” said our English- speaking friend.

On the way back, we stopped by the roadside to have a picnic lunch and broke the spell. An American diplomat produced onion thins and Danish pate. Someone contributed beer. The 20th century came whooshing back as we opened the cans and bottles.